THE AMERICAN SCHOOL CAMPUS until 1945 took shape within a tradition that extends back at least 1,500 years. Its shape effortlessly afforded an environment of security and tranquility in which body and mind (heart and soul) unencumbered by life’s daily pressures and stresses thrived. (Centennial High School Design Competition Entry, Johnson Favaro, February 2024)

We sometimes welcome young people into the office who arrive at work, oddly, with a cultivated, seemingly sophisticated sense of resignation, even dread, often even defeat or just disorientation. They are like deer in headlights.

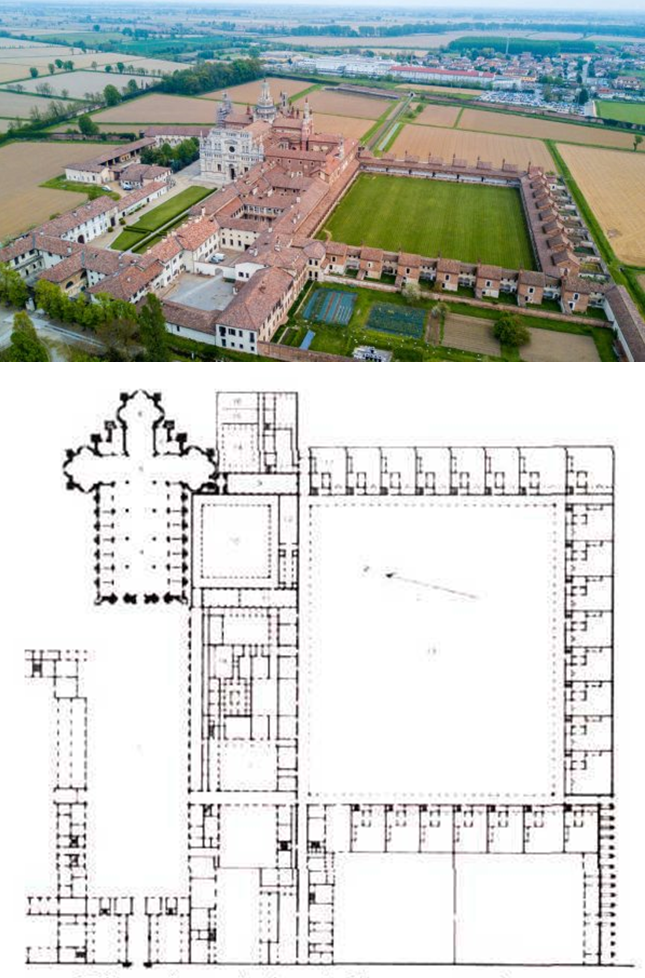

ABBIES AND MONASTERIES of the European Middle Ages were modeled on building types established within the Greco-Roman town planning tradition (temples, agoras and forums) creating microcosms of cities in which both private and public lives circumscribed within the monastic community flourished. (Certosa di Pisa a Calci, Italy, 1366)

THE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS tradition was modeled on the abbeys and monasteries of the European Middle Ages beginning most notably with the founding of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England (Kings College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 1441)

How can there not instead be a sense of anticipation, uncomplicated enthusiasm upon the initiation of a lifelong learning experience, of getting to work on something—finally-—that will be put out there into the real world? While we can’t know for certain, we at least know that what these young people have in common is their having recently attended architecture school. We suspect that their schooling has something to do with it and might ask what goes on in their schooling that would engender such premature and precocious weariness?

PIRKEIT ARVOT roughly translated as “Chapters ( or Ethics) Of Our Fathers” was written in the 2nd century C.E. as a tractate within the Mishnah and was uniquely devoted not to biblical exegesis as is most of the Mishnah but rather to the rendering of advice on moral and ethical matters.

Schools are among our most important institutions and have been for a while. They probably had their origins in the “beit sefer” or “house of the books” of ancient Aramaic and Hebrew societies—spiritual places of learning founded upon the shared desire to figure out what the heck the bible meant. Then in the west came the philosophical academies (most famously Plato’s) in which the topics were morality, ethics, mathematics, and psychology. Then, with the fall of Rome cloistered abbeys and monasteries assumed their place as the centers of learning and remained so for almost a thousand years.

THE END OF INSTITUTIONAL CORRUPTION was among the reformations that Jesus advocated for against the Pharisee/Sicani/Sadducee sectarian establishment most dramatically illustrated in the Temple Incident. Little did he know what kind of institution would four centuries later.be established in his name (The Temple Incident above; the medieval church leadership, the pope and his cardinals, below)

CORRUPTION SETS IN when the display of once meaningful, now meaningless pomp and circumstance associated with outdated traditions distracts from the modern day mission of a church such as the Catholic church, perhaps most flamboyantly illustrated here by members its leadership (Raymond Burke American cardinal in full liturgical regalia, center)

In Italy in the 14th and 15th centuries Platonic academies were re-established by the Medici in Florence among others elsewhere. Also around that time, art academies modeled on medieval trade guilds spread across Europe, then morphed into academies of fine arts. Most famous of these is the École des Beaux Arts in Paris whose hegemony over the art world lasted a few centuries until a century ago when the modern movement threw it under the bus, the “avant-garde” having dismissed it as old school, the word “academy” becoming forever associated with all that is exhausted and irrelevant. Wounded by the assaults and insults and its own stultification, the academy in America limped into the 1930s and 40s until it got absorbed into the universities as schools of architecture, where modernism flourished. The academy became modern, modernism now is the academy.

THE ACADEMY as originally established by Plato and others was originally a community of curious minds engaged in the shared pursuit of sound reasoning on topics of morality, ethics, politics, psychology, and mathematics. The closest we have to it now is the university in which showmanship, grandstanding and usury often distract from and overshadow the seriousness of the academic project.

In the 1970s and early 80s there were good reasons to be involved in the architecture schools, two of which were 1) it was where, however briefly, all the reasoned re-thinking of modernism was happening in a serious way; and 2) the post war economic surge of building in America had ended, stagflation had set in, there was very little work, it was a steady source of income. Architecture schools in universities were dynamic places for a while but then they degraded.

THE RENAISSANCE WORKSHOP model of apprenticeship in which novices mastered their trade, craft or art under the mentorship of a senior colleague (or “master” in the now-outdated terminology) ossified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when academies of fine arts such as the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris devolved into closed single-minded and excessively hierarchical societies. (Medieval/Renaissance workshop above; Ecole des Beaux Art antiquities gallery below)

THE BAUHAUS was founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius to modernize the workshop/academy model incorporating machine-made materials and manufacturing techniques into the practices of art, design, and craft--all within a lively environment of inquiry and invention. (Ecole des Beaus Art drawing studio above; Bauhaus workshop below)

More than the humanities or the sciences, the university environment is for the study of architecture a particularly harmful environment—in which it is especially inappropriate that it is only your peers who are your audience. It distorts your view of who you serve, who are as an architect, anyone but your peers. And yet to survive within the academy, prestige among your peers is crucial. And even as it is only your peers who you want to impress you still crave relevancy beyond your peers, for without it the academy and your prestige (and any hope of securing work outside of the academy however unqualified for it you are) withers.

HOWEVER WELL INTENTIONED Gropius was when he arrived at Harvard University in 1937 to reform its architecture school (which when he arrived was still operating on the model of the Ecole des Beaux Arts) on the model of the Bauhaus it was an effort that was bound to falter within the American university setting

HOWEVER WELL INTENTIONED that a school of architecture (or landscape architecture, urban design, city planning or real estate development) would arrogate to itself the responsibility to solve or even comment on political or economic issues is itself a corruption of the institution’s purpose which is above all else to teach the craft of architecture. It is up to the student to decide how best to work (or not) within any social, political or economic environment guided by their own moral clarity and authenticity of purpose. (Sarah M Whiting, Dean of the Harvard GSD in a message to alumni, September 2022).

To compensate you pronounce on areas outside of your discipline. You delude yourself that from the safety of an architecture school you participate in solving the world’s problems—be they social, racial, ethical, or environmental—without participating in the world’s problems. You want to sound experienced without having experience. Your solutions never come to pass, but it does not matter because it is only ever a performance and peer prestige is the applause.

THE TRADEOFF presented here is a false choice forced upon young people by the corruption of both the academy and the corporation, and founded upon the false dichotomy and by now cliché of the “sell-out” and the “starving artist” (“How To Be in an Office”, Symposium at Sci Arc in 2022)

THE EXTRACTION OF FREE LABOR from students with the promise of scholarships, letters of reference and employer recommendations is nothing less than the unconscionable exploitation of the apprentice/teacher relationship that undermines the mission (and probably spells the end) of the current iteration of the workshop/academy/school model.

Along the way captured by the academy’s insularity and the corrosive social dynamics within it, exploited by the inside-game of competing self-interests –rarely in support of the academy and more often at its expense-- corruption sets in. And instead of thriving on agency what festers is impotency. We ought not wonder then how it is that students having sublimated such powerlessness arrive at the beginning of their careers deflated and defeated.

THE EPIDEMIC OF MISTRUST that has infected institutions nationwide is widespread and endemic to a climate of exploitation and distortion by the individuals within them.

TO PRACTICE OR TEACH within the current model of both the profession and the academy is as an architect a choice. If the choice is to teach, then teach without regret. If it is to practice, then teach through your practice. If it is to practice by teaching, you compromise both and you are compromised by both.

We do not regret the experience of the schools we attended; we are in part who we are because of them. But we have over the forty years we have spent in self-imposed exile distanced by and from the architecture schools (at first reluctantly and now happily), come to accept that it has been enough to have created our own academy--our monastery, our practice -- in which ideas and their execution are debated, our values shared but not so much as to have devolved into some kind of pointless echo chamber and instead evolved into a lively place in which to practice and learn.

AS A MEANS OF SELF PROMOTION teaching in American architecture schools is by now a well-known practice which by the very fact of its corruptive nature will inevitably subvert the schools’ credibility thereby undermining the purpose of the practice.

LEARNING TO BE HUMAN or at least a better or better skilled human was the purpose of the Platonic Academy that was successfully channeled by the guilds and workshops of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and then the fine arts academies and for a while the architecture schools, but no longer.

It is only with practice from which ideas, points of view and values—and crucially a sense of agency in the world--- emerge. We are all, no matter how well educated, autodidacts. The role of school should be to provide a place in which self-initiated learning can flourish but at least as far as we can tell it is only in practice that it does. This is the kind of learning that after only a few months our exhausted beginners begin to embrace and consequently thrive.

THE PRINCIPLE OF THE LIBRARY as the heart of a school, its campus and community, is both obvious and fundamental and yet it has been all but forgotten by a profession distracted by contemporary obsessions.