AN ANCIENT NORM is applied here in which a new building is shaped to shape the open space around and within it in a manner that is distinct from how for the last century we have become accustomed to seeing buildings—that is, as free standing and isolated within amorphous, boundaryless environments. (LAUSD Fairfax High School New Physical Education and Arts Building and West Campus Redevelopment Project Design Build Competition Entry; Top to bottom: new gymnasium and arts classroom wing, new quadrangle, aerial view of new building and quadrangle; Johnson Favaro, 2024)

We were not long ago the recipient of what was intended as a compliment in evaluation of a competition entry for a school district here in Los Angeles that went something like “We appreciate your out-of-the-box thinking” to which our response (which went unsaid) might have been “What? We thought we were thinking entirely within the box.”

TOP olrat - stock.adobe.com BOTTOM Google Earth aerial

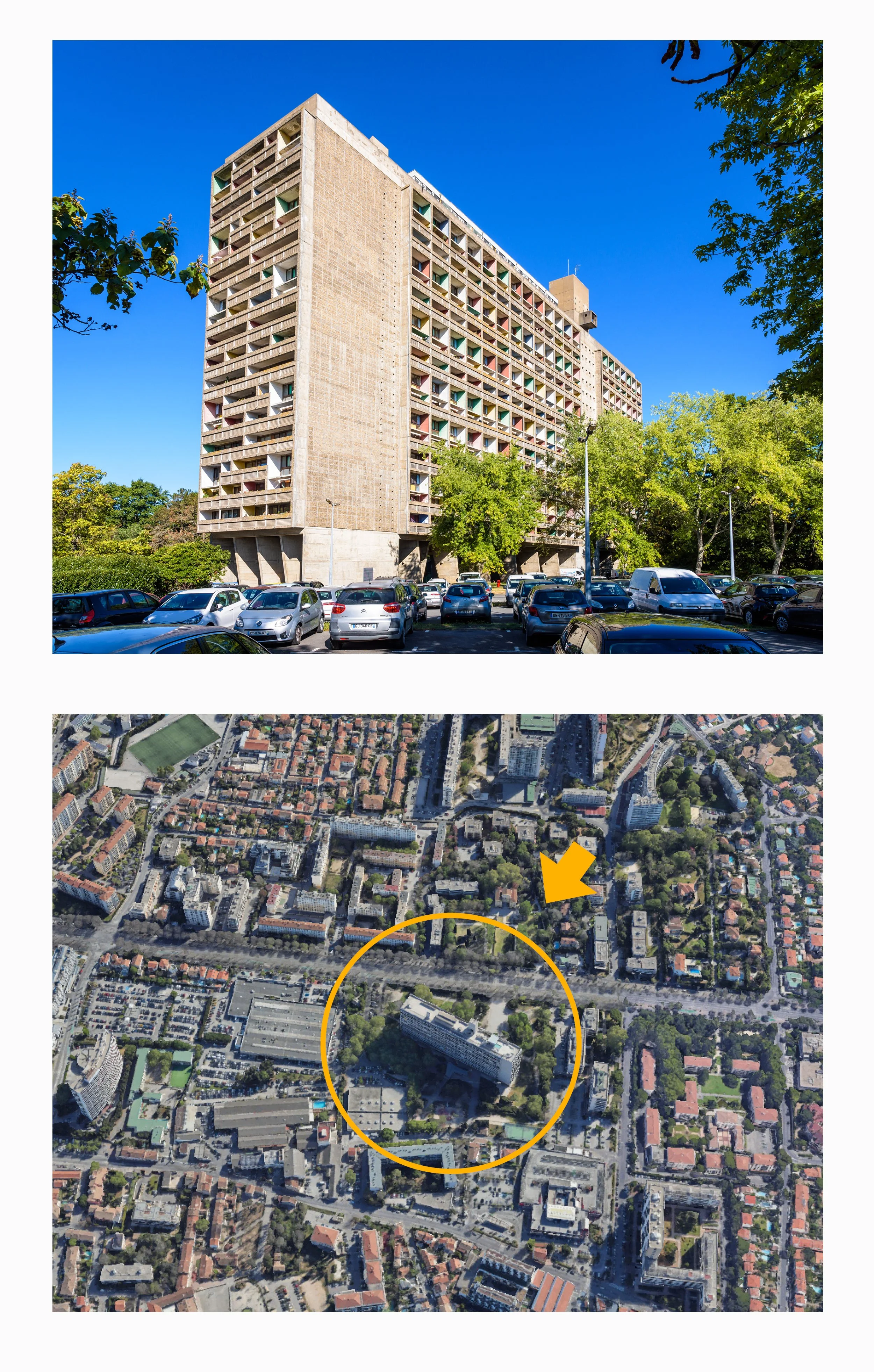

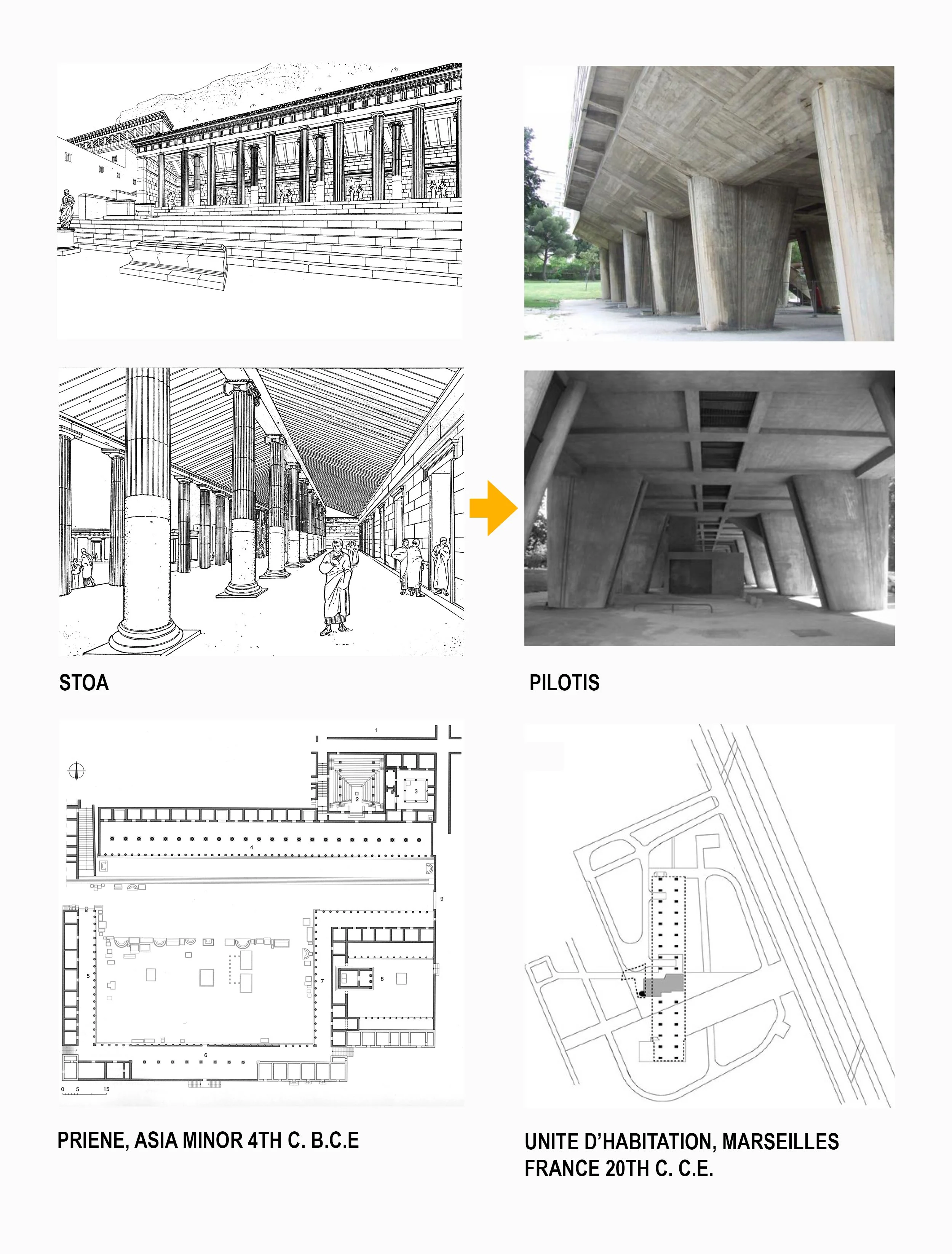

THE IDEA OF A HOUSE IN A TOWER IN A GARDEN (AND A PARKING LOT) is a relatively new one (just a century old) and as accustomed as we are to (and by now repelled by) the idea it must have been astonishing to behold and and exciting to experience in 1952. (Unite d”Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

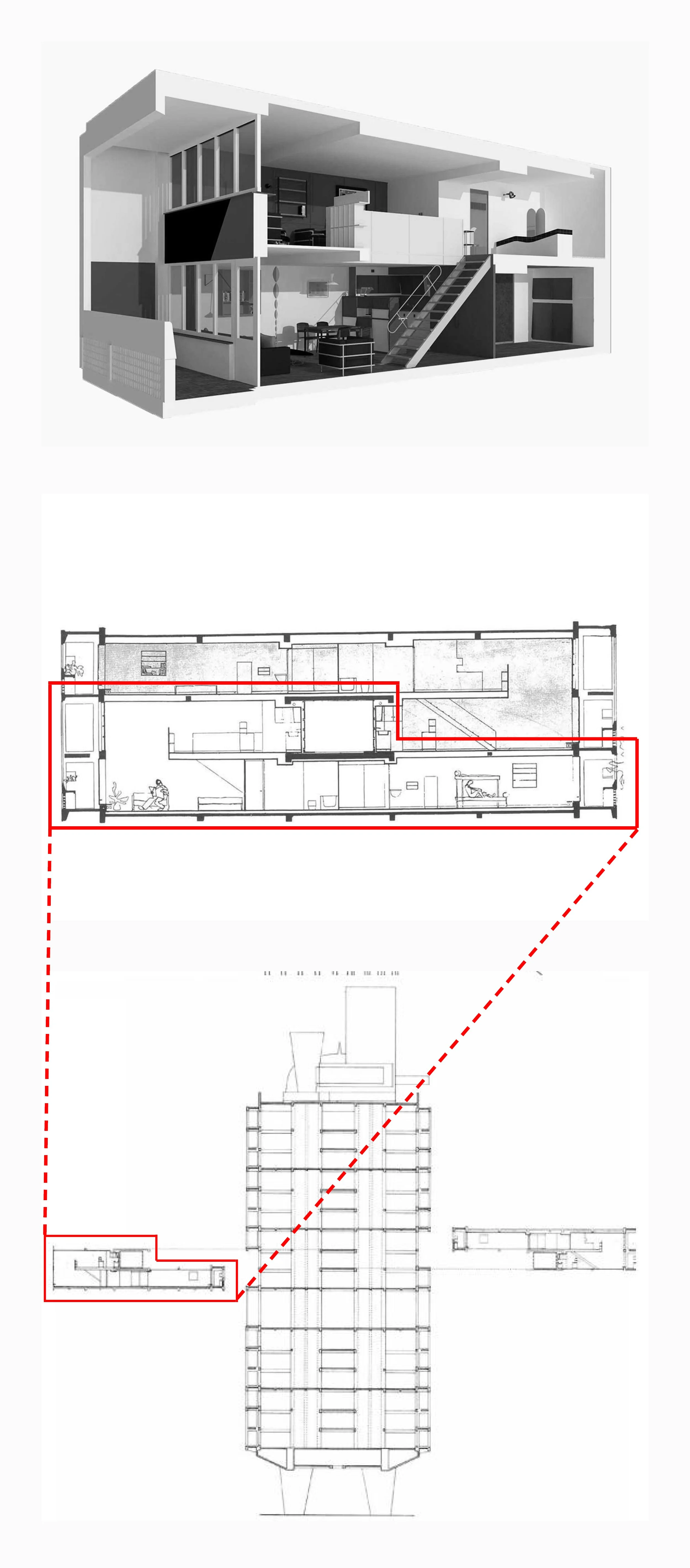

STAND ALONE AND SELF-SUFFICIENT is this building intended as it was by its author to provide for all its residents’ daily needs—housing, physical activity, food-- without recourse to a neighborhood or a city: hence the name, “Unite”, or united, but which could have also been “Ile” or island, or in Jeanneret’s words a “vertical village.”. (ABOVE Axonometric diagram with one residential unit “pulled out”; BELOW site plan; Unite d”Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

This was a design build competition and the box outside of which we were supposedly thinking was the set of design criteria with which we had been presented as the basis for what we were to submit. From our perspective the criteria had foregrounded pragmatic priorities (utilities, interim housing and construction staging) which while are important are not what should have driven, nor come at the expense of, the planning and design of a humane campus environment. But what is a humane campus environment or any kind of built environment and why are we now so incapable of realizing one?

Original Design Reconstruction Le Corbusier (via Wikimedia)

SELF CONTAINED as a house within a tower each residential unit has as its “yard” a double height terrace that takes the place of the old school balcony and yet still contained within the volume of the tower. (Unite d”Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

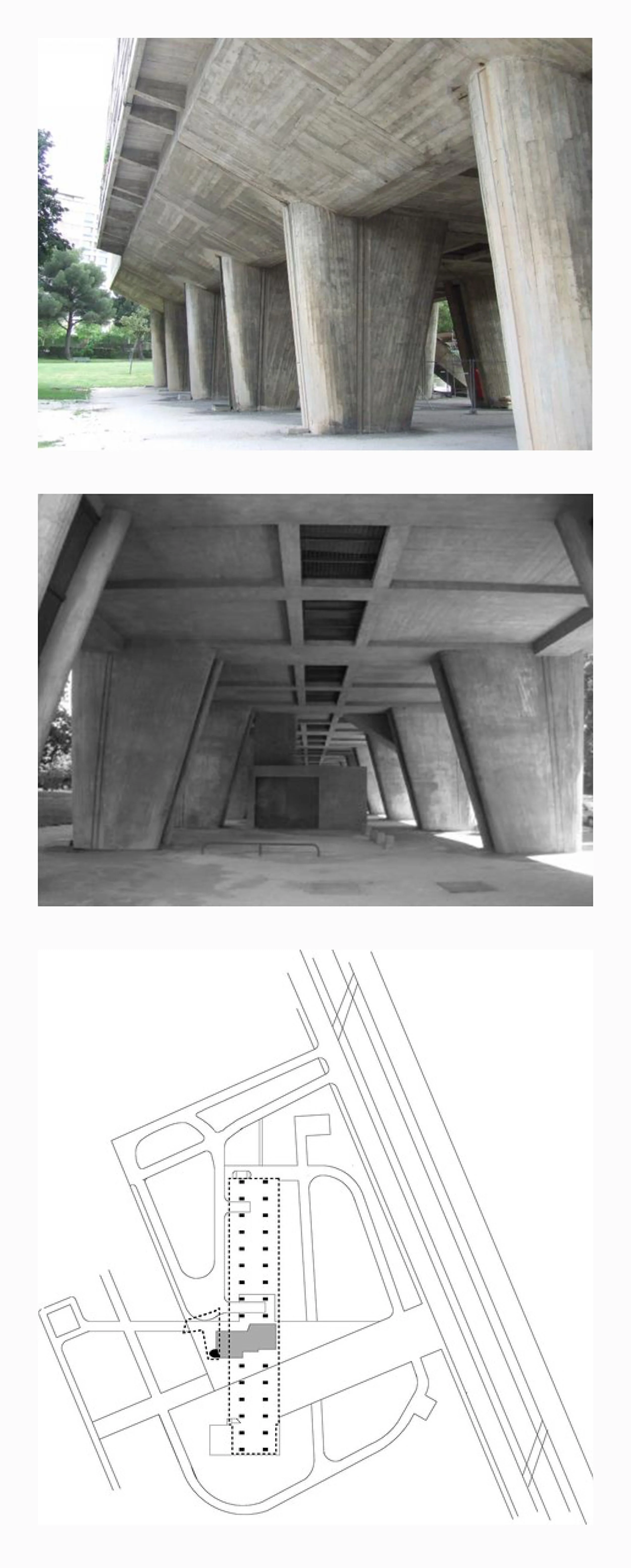

A COLONNADE TO NOWHERE is the ground floor of this building which has been expressed as a kind of primitive arcade through which, presumably, passage is accommodated, by whom and for what purpose it is not clear. (Unite d’Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

It must have been astounding in 1952 to have first encountered an apartment in the Unite d’ Habitation, Charles Jeanneret’s residential complex in Marseilles—the open floor plan, the double height living room, its spacious balcony. Today it’s hard to imagine such an interior as anything other than standard fare—and not much better than any apartment on any street in the heart of Paris. Most of us may even argue that any apartment in the heart of Paris-- especially one that has incorporated some of the innovations of Jeanneret’s Unite--is better than one on the outskirts of Marseilles. What was once the enemy, the city, is now our friend, even though most of us now would not know how or even where to begin to build what was once the norm.

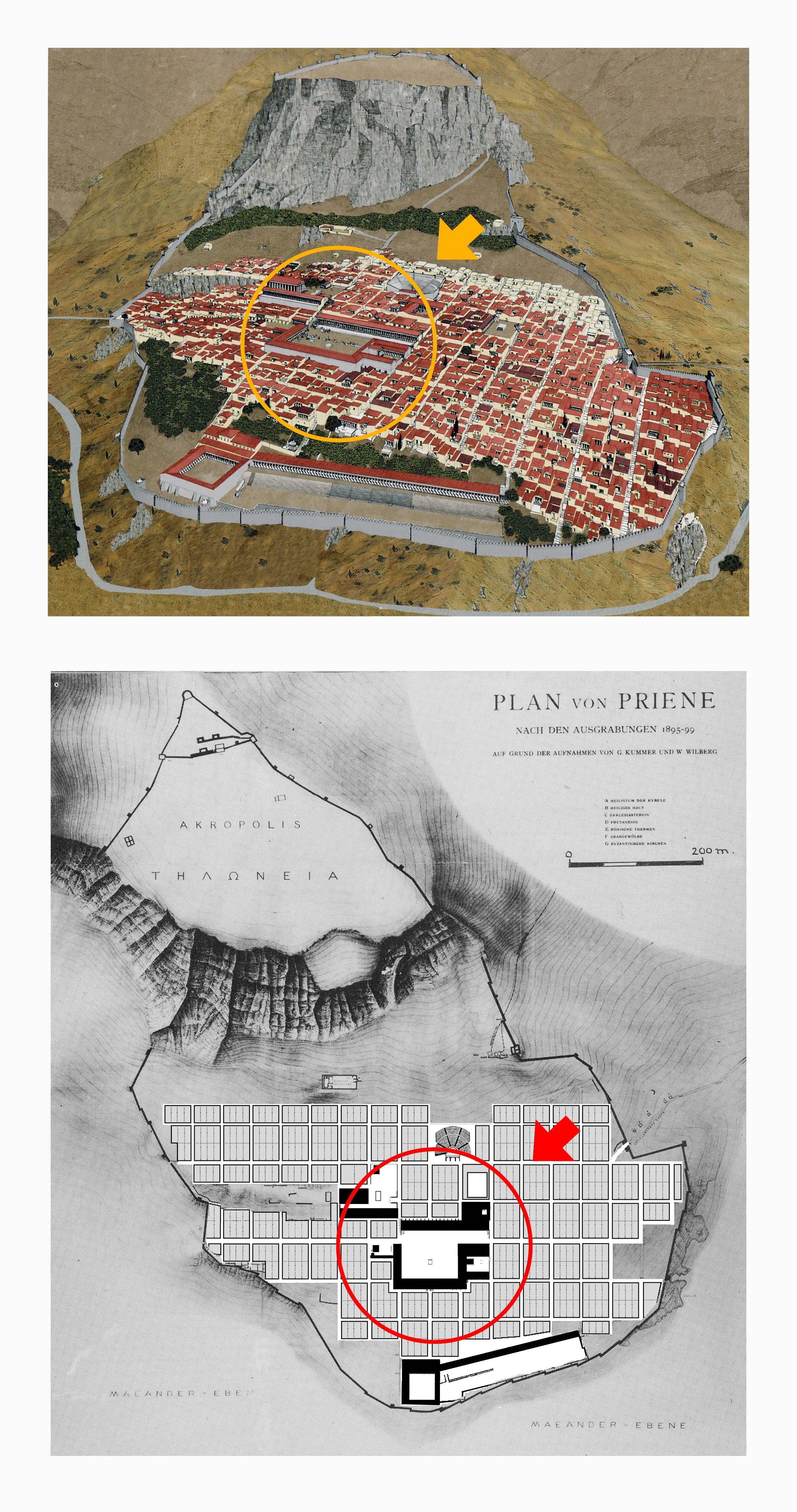

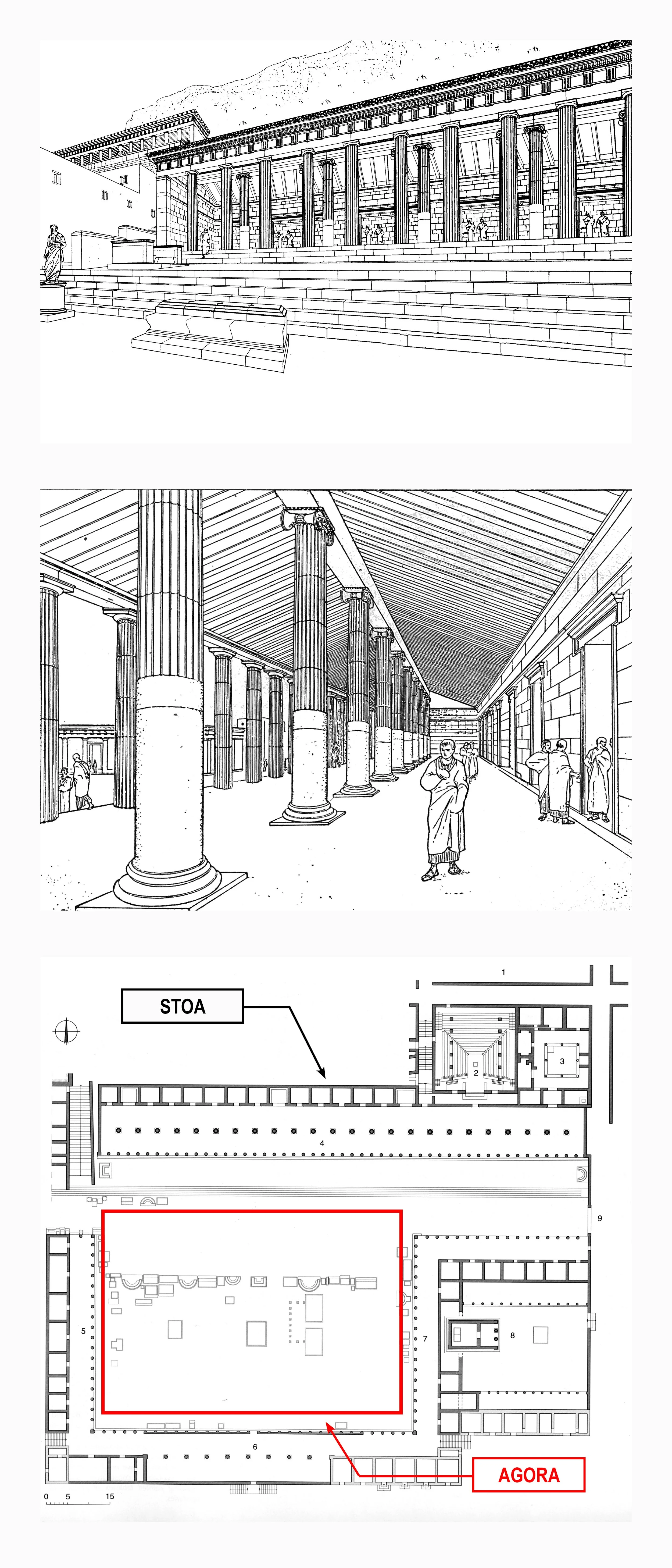

THE MODEL OF THE CLASSICAL CITY, pedestrian in scale, articulated into two main parts, one collective (streets, squares and monuments) the other individual (housing and commerce) reached its apotheosis in Hellenistic Greece roughly 2500 years ago, a model that endured across the world until 100 years ago. (Priene, west Asia Minor, present day Turkey, 4th century BCE)

That astonishing achievement of mid-century Marseille fueled momentum for a movement at the helm of which Jeanneret and his contemporaries stood--modernism’s avant-garde-- which despite the short-lived efforts toward its reform in the 1960s, 70s and 80s yielded a nearly-century-old game of one-upmanship in which The-More-Astonishing-The-Better always wins. The practice of architecture as a fine art has devolved into the merely performative while what was once considered architecture as a pragmatic, social, and urban art has gotten lost in the excitement.

THE BUILDING’S NOT THE THING that was considered primary in the configuration of these colonnades (stoa) but instead the agora--the open space--formed by the colonnades. (Priene, west Asia Minor, present day Turkey, 4th century BCE)

For a few thousand years what was the norm in the making of buildings and cities (and campuses) was dependent on only a few immutable fundamentals: the limits of materials and of the human body. We could only walk so far, and climb so high, build so high, and span so far. Streets were enclosures, places to be as much as to pass through—they were for people, not cars. They arrived at squares, places of gathering and repose, outdoor rooms. And except for the occasional monument (temple, church, theater or city hall) buildings merged into blocks—whose main purpose was to form streets and squares. Most people lived within walking distance of everything they needed to live.

AN AGORA IN MINIATURE the home (receiving its daylight not from its perimeter but from its core) further articulated collective and individual parts, and in its accumulation with other homes created the blocks which in turn formed the streets and squares. The home, the individual part of the city, dissolved into the background while the streets, squares and monuments, the collective part, assumed the foreground. (Priene, west Asia Minor, present day Turkey, 4th century BCE)

This was the norm and to be reminded of it need not take on the moral tone to which we are sometimes subjected to be accepted as true, nor is it merely nostalgic or anachronistic to claim it to be so—for as a norm that is related to the scale and the mobility of the bodies that we still all inhabit it remains undeniably true. Nothing in the last century about the human body has changed and, in this respect, we are all the same no matter our color, culture, code or creed.

THE ROLE OF THE COLONNADE in service to something larger than itself in the 4,900-year-old norm has by this modern architect been subverted.

But technologies have changed—with them we can build higher, span further, move farther and faster, and climb higher. We have been experimenting with them for over a century now with mixed results at best. We have gotten occasionally spectacular outcomes, mixed in with generally inhumane environments.

BY 1950 MODERNISM’S INVERSION of a 4,900-year-old norm was complete with the foregrounding of the individual realm (the block) and the backgrounding of the collective realm (the square)—a way of living that after only a century most of us believe is the only way to live (LEFT Priene, west Asia Minor, present day Turkey, 4th century BCE; RIGHT Unite d’Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

Were what we might now call ‘classical” or “European” or “traditional” cities and campuses merely accidents of history? Are they, because we no longer build buildings with the same technologies, also no longer relevant? Is there really nothing to be learned from them? Are the views afforded by super tall buildings, the exhilaration of super long spans and extravagant shapes, the freedom of fueled transport, and the luxury of extended or individually owned open space within a city or on a campus worth the trade-offs? Need there be trade-offs?

TOP LEFT: Opium Creative- stock.adobe.com, TOP RIGHT: areefa- stock.adobe.com, BOTTOM LEFT: Ekaterina Belova- stock.adobe.com, BOTTOM RIGHT: olrat- stock.adobe.com

WAS IT WORTH IT, DID IT WORK? are questions that the marketplace seems to have already answered most people preferring an apartment on a street in Paris over one in a housing block overlooking a parking lot in Marseilles-- or anywhere for that matter. (LEFT Paris street and apartment, ca. 19th C CE; RIGHT Unite d’Habitation, Marseilles, France; Charles Jeanneret, 1952)

When we disregard norms and the diversity of traditions across which they have been interpreted, not to mention the untapped possibilities with which they still can be interpreted, we pay a price, that price being confusion. We foreground either those aspects of a building that we can calculate (facts) or get excited by (fantasy). We box ourselves in, those boxes being either “utilitarian” or “award-winning.”

TOP archer10 (Dennis) (via Flickr) BOTTOM Pompeii, Italy; 1st C BCE (via Wikimedia)

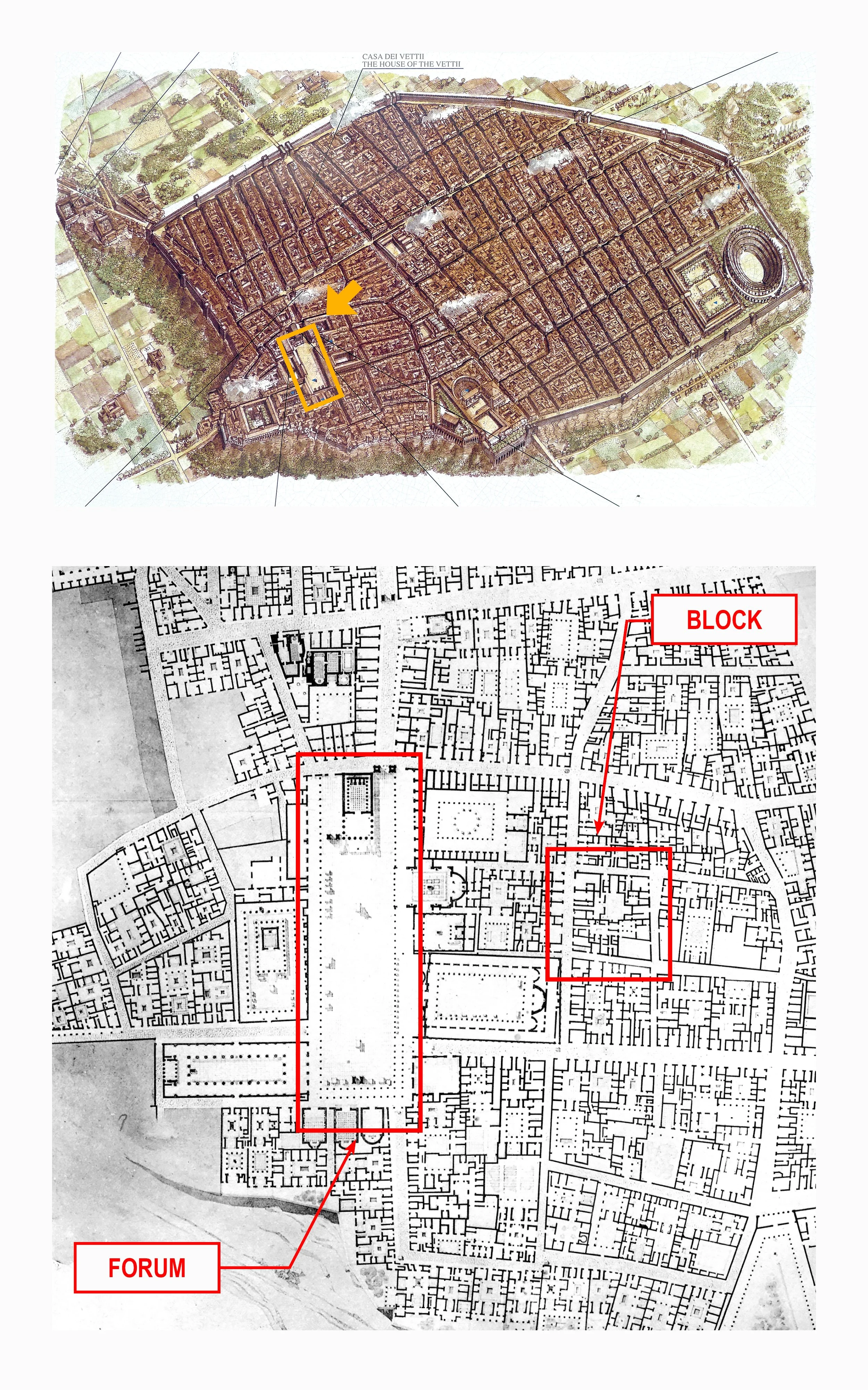

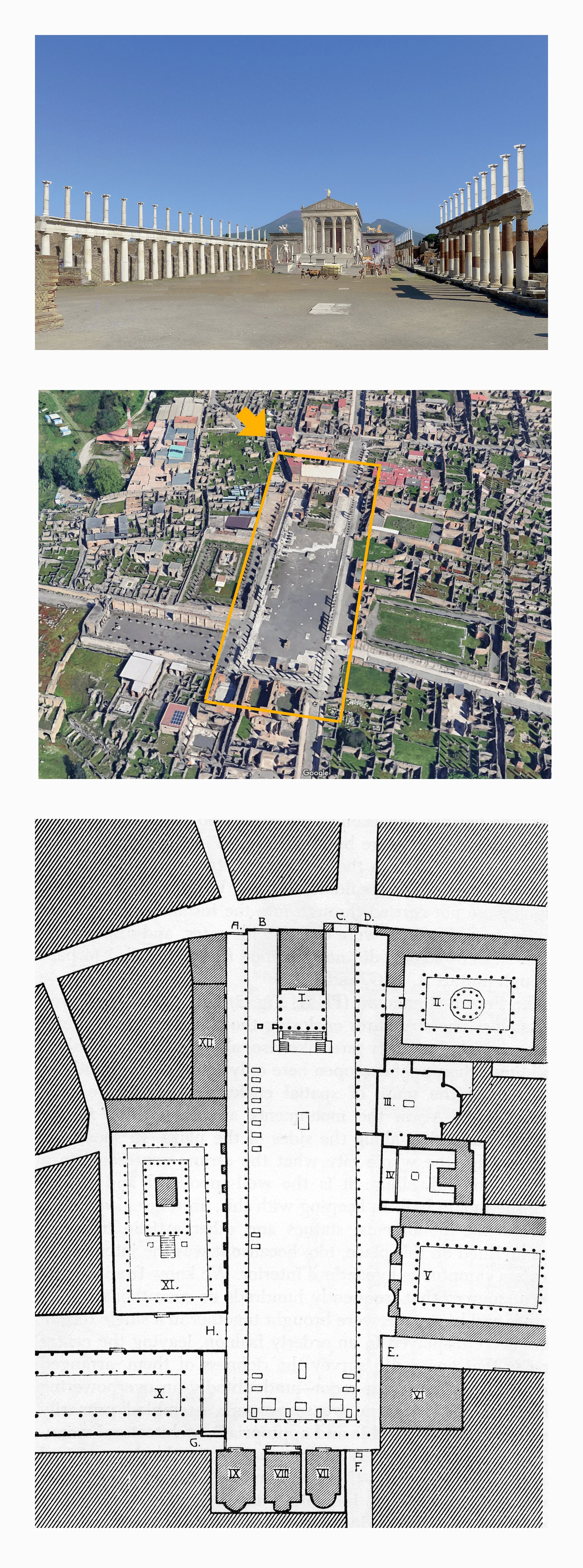

THE ROMANS established cities across the Mediterranean and Europe that were modeled on norms that the Greeks had perfected, albeit in a more rigid, more enclosed manner that was less sensitive to the underlying and surrounding geography.

THE FORUM of the Romans assumed the role of the agora which in its later iterations would over the next 2,000 years become the piazza, plaza, place and town square of cities across the western world.

THE 2,000 YEAR OLD NORM that had reached its most realized expression in Hellenistic Greece was reimagined in the 16th century in Florence, Italy as a government office building (Uffizi, Giorgio Vasari, ca. 1560, Florence, Italy)

A school campus is little more than a city in microcosm and there are stores of knowledge accumulated over millennia of experience from which to draw upon in the making of a city or a campus. They are called norms. They are normative because they work, and when we ignore them, when we venture too far outside of the box as today’s performative architects so consistently do, we lose our way.

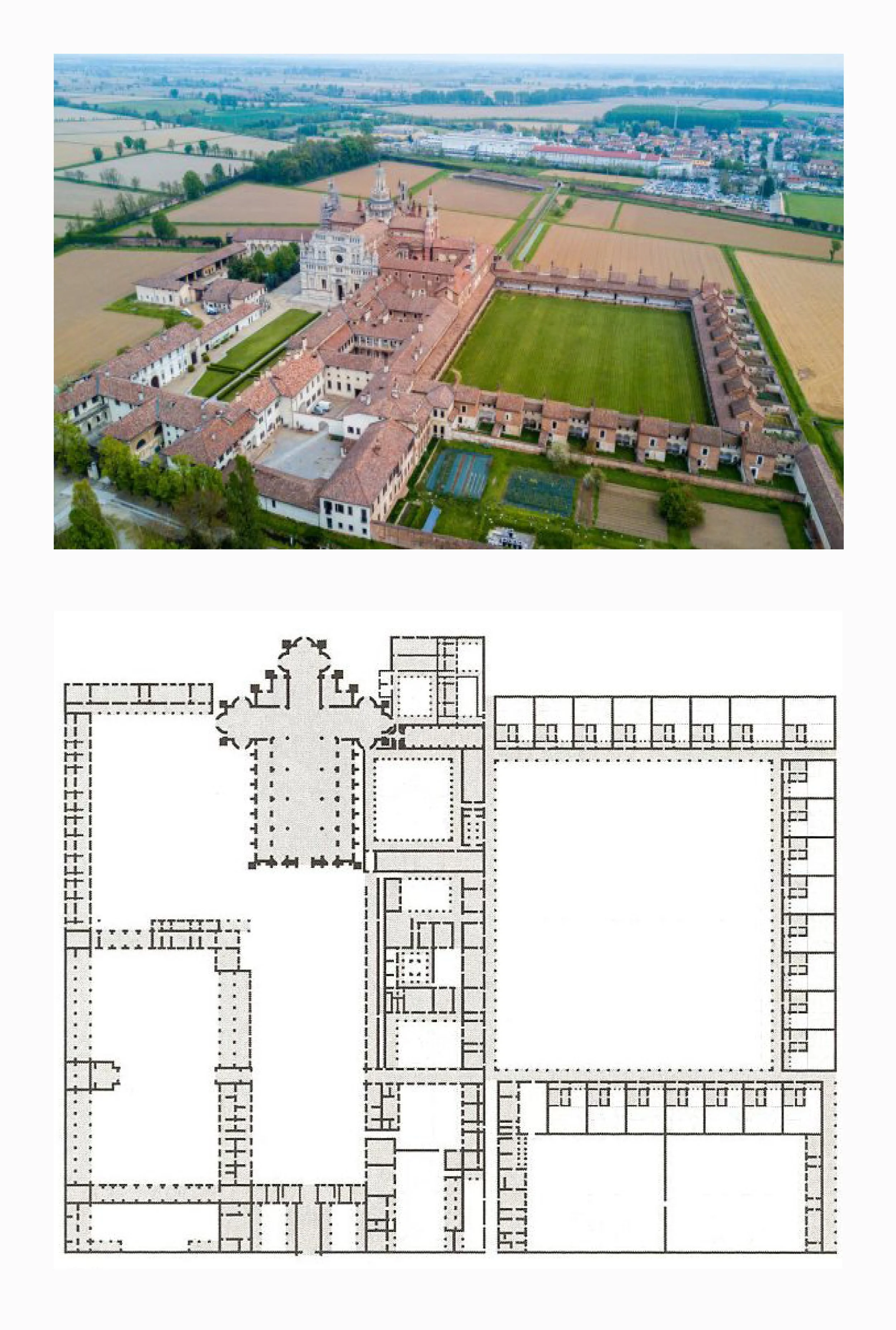

FOR A THOUSAND YEARS between roughly 500 CE and 1500 CE monasteries of Europe were stewards of the norm, the cloister assuming the role of the stoa, the courtyard that of the agora (Certosa di Pavia, outside of Milan Italy ca. 1400 BCE)

THE MISSIONS OF CALIFORNIA were—all 21 one of them—configured on the model of the European monastery, maintaining the practice of foregrounding the collective part (the church and the courtyard) while backgrounding the individual part (the residences and work spaces) (Mission del Rey, San Diego, CA, 1798, above; Mission San Juan Capistrano, San Juan Capistrano, CA; 1776, below)

LoveMetaverse / shutterstock.com

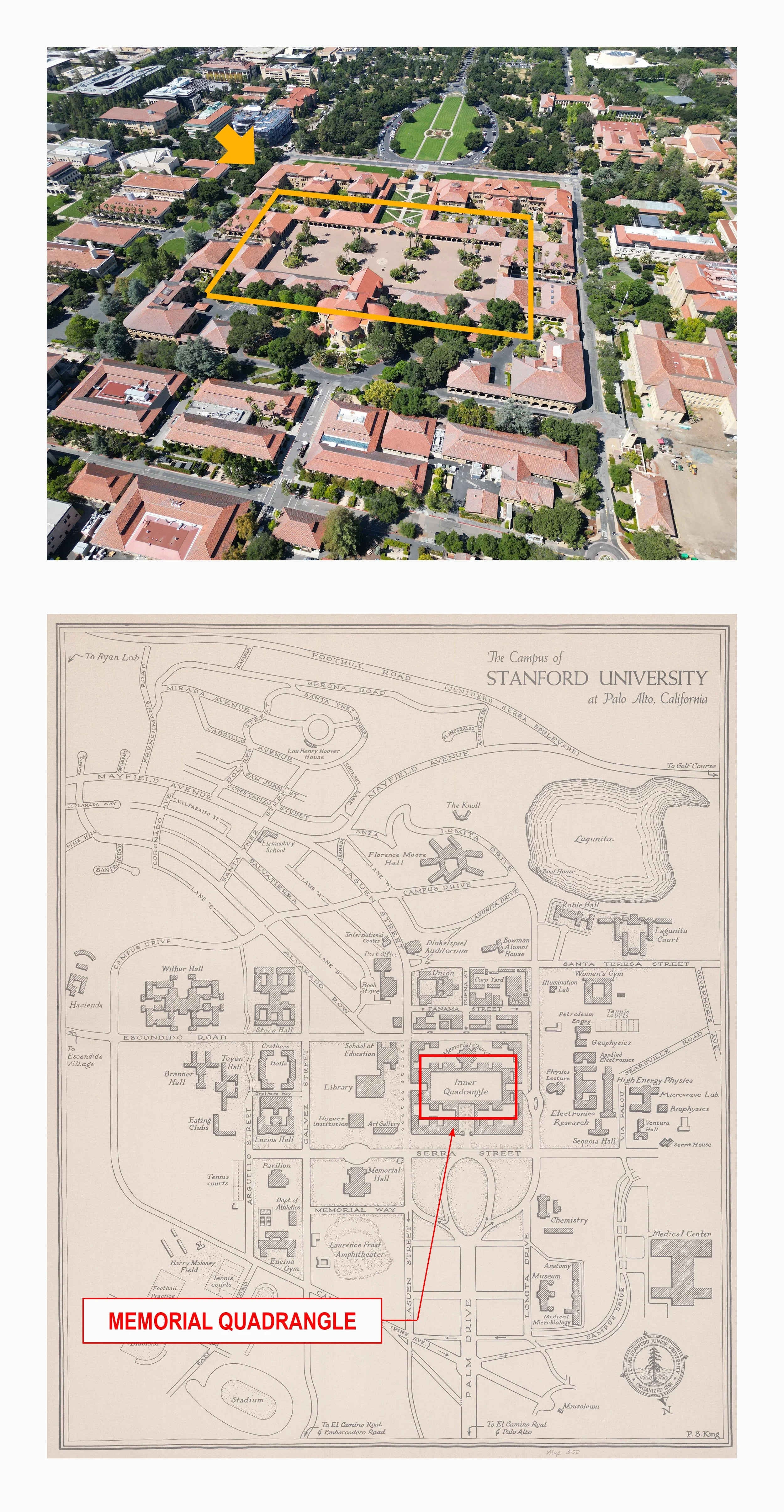

AMERICAN COLLEGE CAMPUSES such as Yale and Princeton on the east coast were modeled on northern European university campuses such as Oxford and Cambridge which were themselves modeled on the monasteries of northern Europe, while those on the west coast such as Stanford and Caltech were modeled on the monasteries of southern Europe. The universities established the planning and design model (and norms) for school campuses across the country (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; 1815-1906)

There is another way. Architecture can be both pragmatic and amazing. And it has been in pursuit of such a goal that we have aimed our practice, one in which we have sought neither to ignore nor be trapped by long established norms and instead to innovate within and adjacent to them. Though we now realize, it has also been, in the context of how architecture is practiced today, an entirely against-the-grain kind of practice.

DON’T BOX ME IN by dropping a bombshell of a building in the middle of campus without any regard for what’s left around it. (LAUSD Fairfax High School P.E./Arts Building Design Build Site Plan Criteria Diagram above; 3-D diagram of LAUSD prescribed building site middle; 3-D diagram of Johnson Favaro proposed building site below; 2024)

OR GO AHEAD BOX ME IN just in a different way by configuring the building to form the perimeter of and shape the more important open spaces of campus, foregrounding the collective part of campus—the quadrangles and courtyards-- while backgrounding the individual part-- the rooms and support spaces. (LAUSD Fairfax High School P.E./Arts Building Design Build Competition Entry; Los Angeles, CA, Johnson Favaro, 2024)

SHAPED TO SHAPE, the new building configures to form affirmatively designed open spaces within and around it. (LAUSD Fairfax High School P.E./Arts Building Design Build Competition Entry; Los Angeles, CA, Johnson Favaro, 2024)