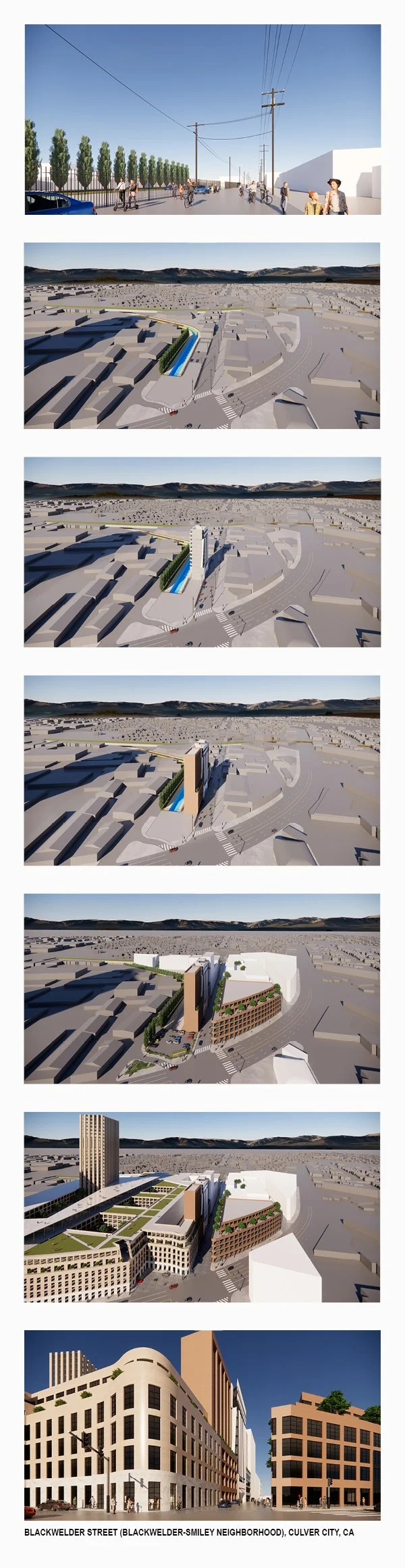

CATALYTIC, INCREMENTAL COMPACT DEVELOPMENT in its accumulation provides the blueprint and roadmap for the emergence of true urban neighborhoods within the Los Angeles metropolitan area. (Blackwelder Residential Development Preliminary Study, Culver City, CA, Johnson Favaro, 2023)

I live in a suburb that is an urban neighborhood a few miles from downtown in the middle of a metropolis.

Say, what?

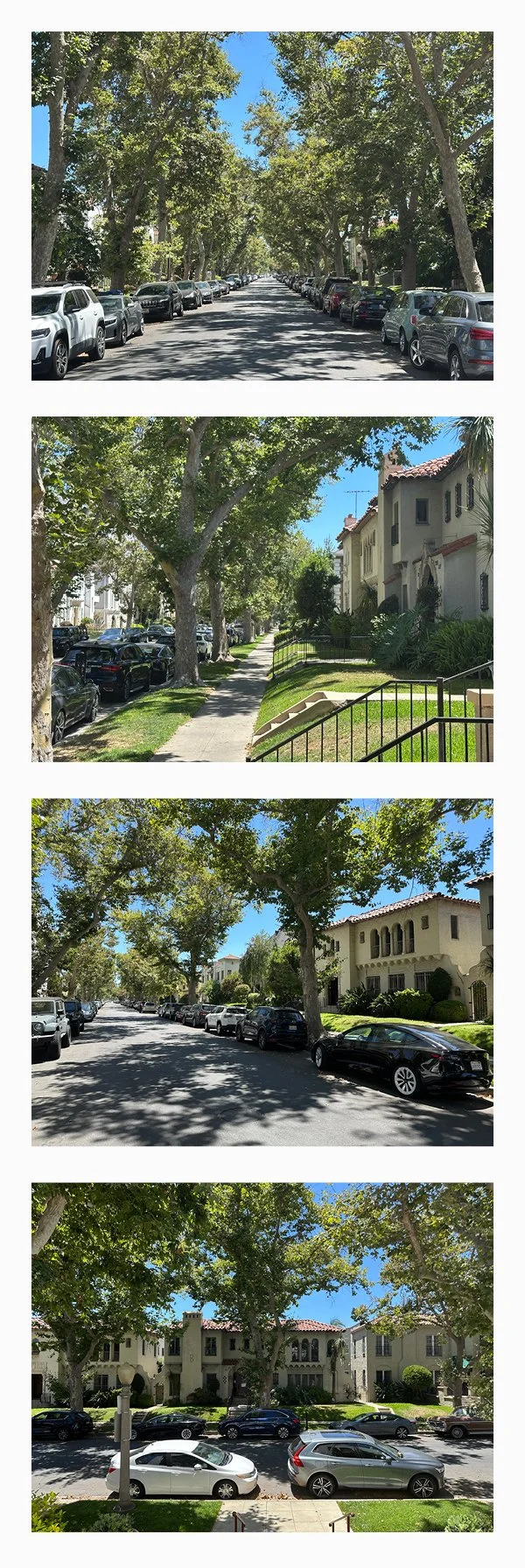

The downtown near where I live is situated within the city of Los Angeles, the metropolis is the county of Los Angeles. The neighborhood where I live was built in 1926. The street on which I live is known for its quaint, tree-lined character.

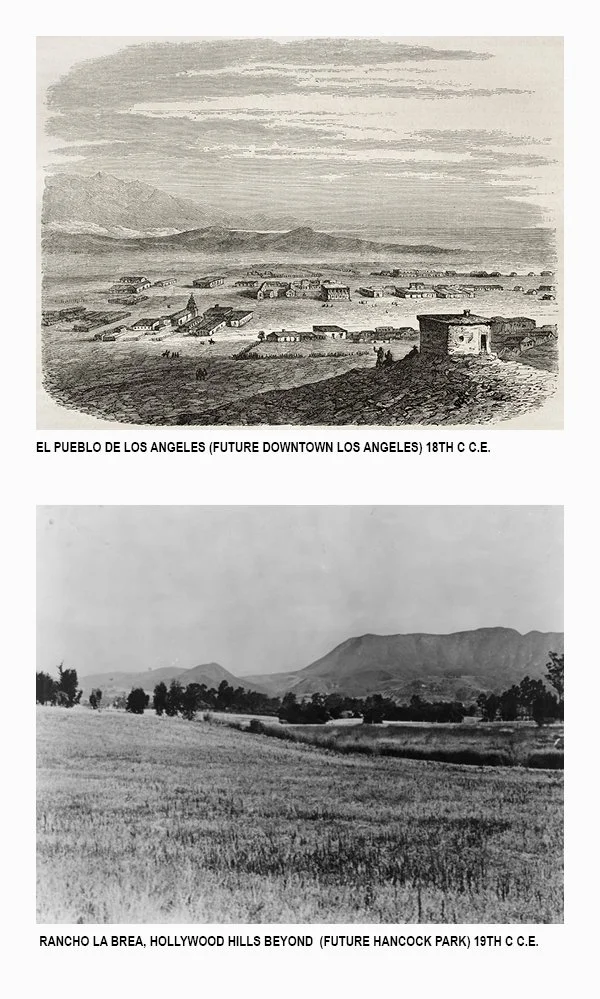

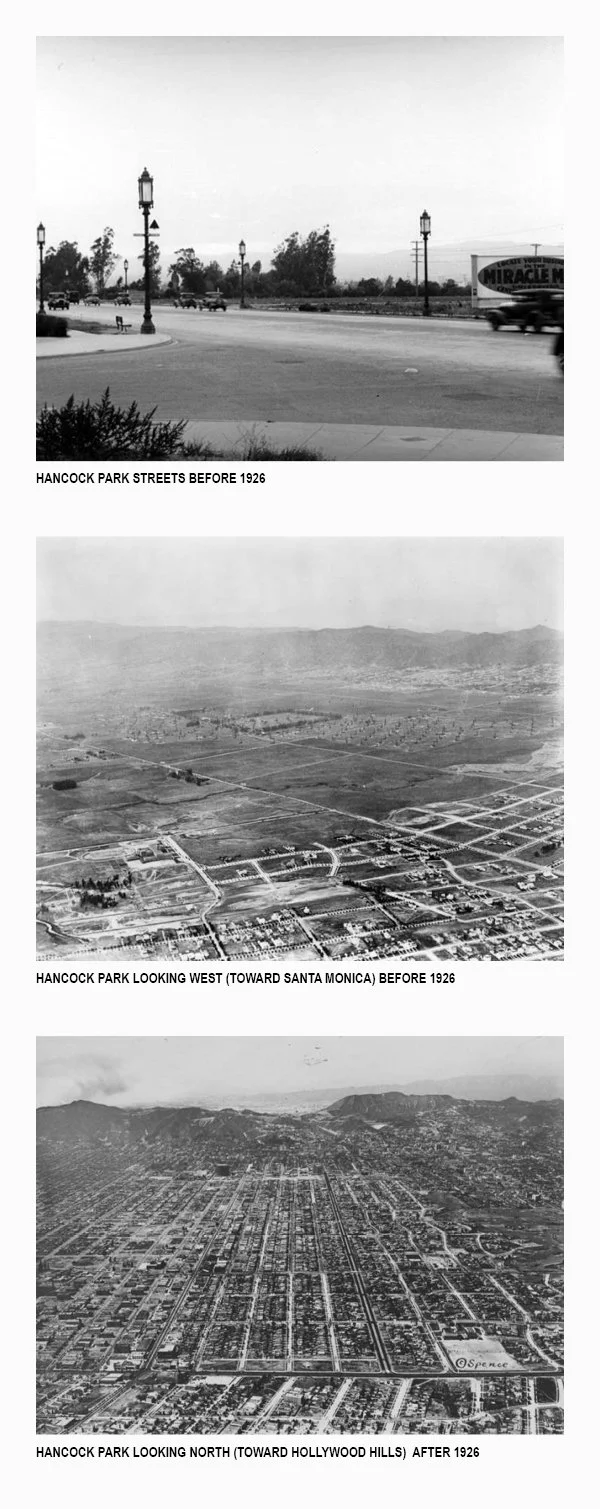

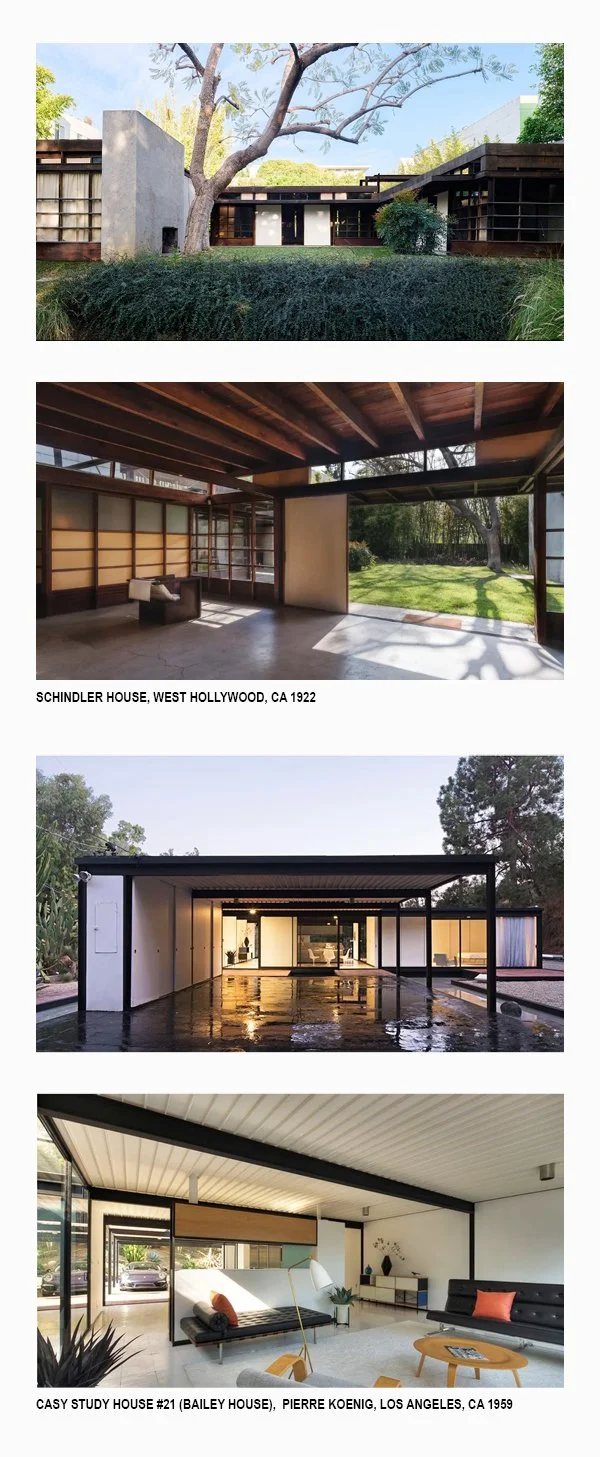

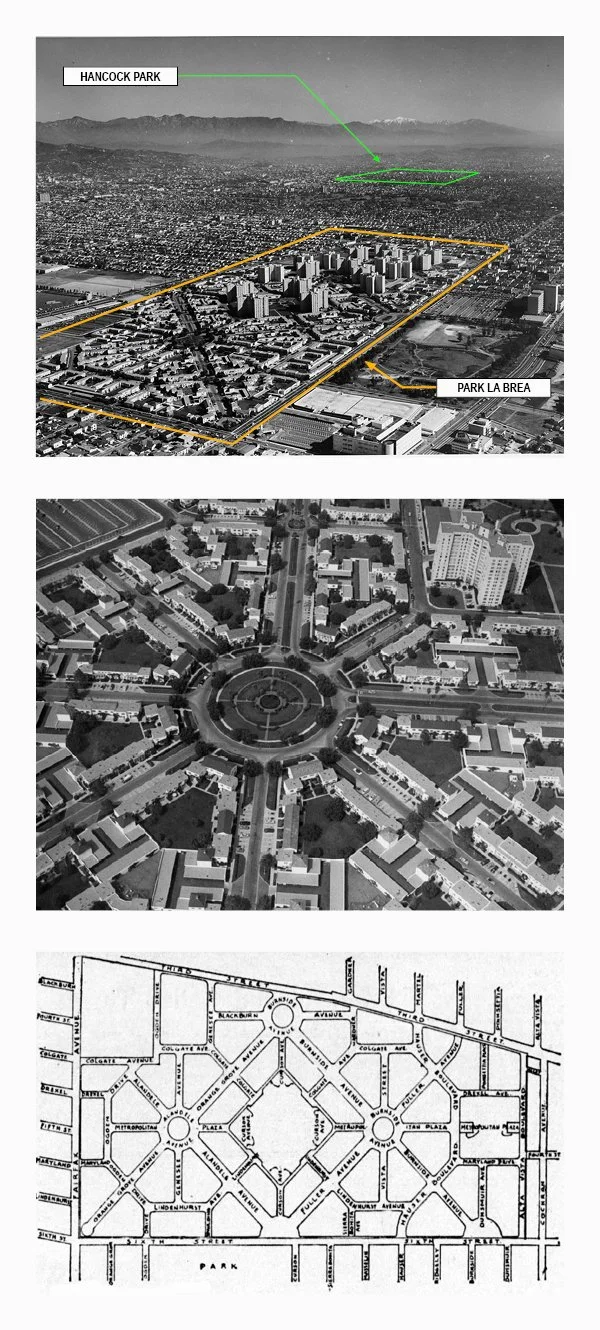

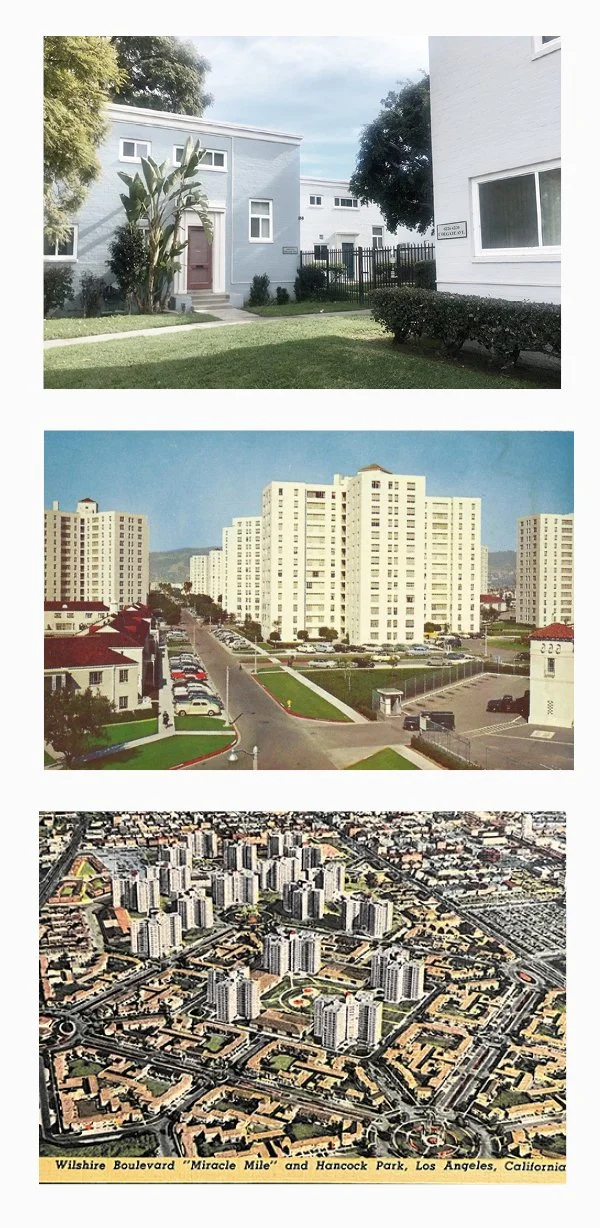

NOT REALLY A PARK the 1920s era Hancock Park development nevertheless stands out as a rectangle of green within the vast stretches of pavement and roofs of central Los Angeles.

The 1920s was a prosperous era in Los Angeles. Railroads had arrived fifty years earlier and plentiful water just fifteen years earlier. The movie industry was birthing, agriculture and manufacturing were burgeoning. What was only recently a cow town now boasted public transit and wide boulevards filled with cars, fantastic wealth and spectacular buildings.

THE LACK OF WATER held back the expansion of Los Angeles which was until Mulholland’s engineering feat of 1909 little more than a Spanish/Mexican “pueblo” on the site of what is now “downtown.”

RAPID EXPANSION of the metropolitan area over the last century, typically described as “first growth,’ occurred entirely on undeveloped land upon first of which were laid out streets and electricity, a relatively novel way in which to originate a city.

Fifty years prior, just as the railroads were arriving in L.A,. George-Eugene Haussmann transformed Paris into a grand, gracious, boulevard-laced, café-lined, tree-studded urban phenomenon. Two decades after the 1906 earthquake San Francisco had rebuilt itself, guided by principles of the City Beautiful movement that were inspired by Haussman’s Paris, principles famously adopted by the 1909 Chicago Plan of Daniel Burnham and Edward Benett and which would until 1929 guide the planning and design of cities across America.

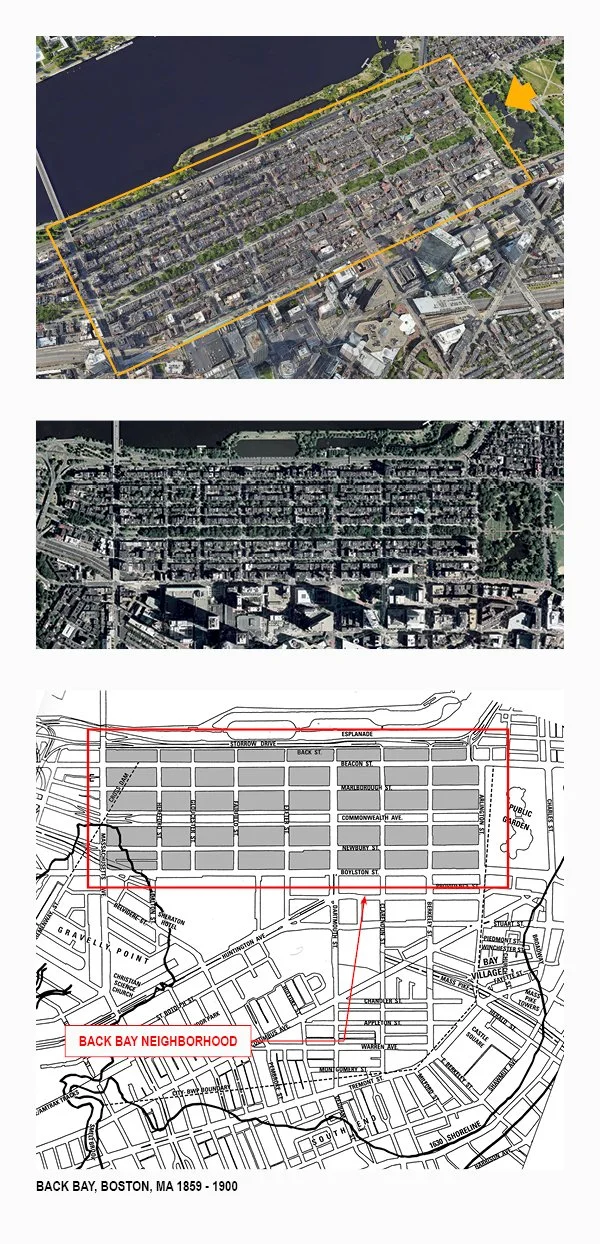

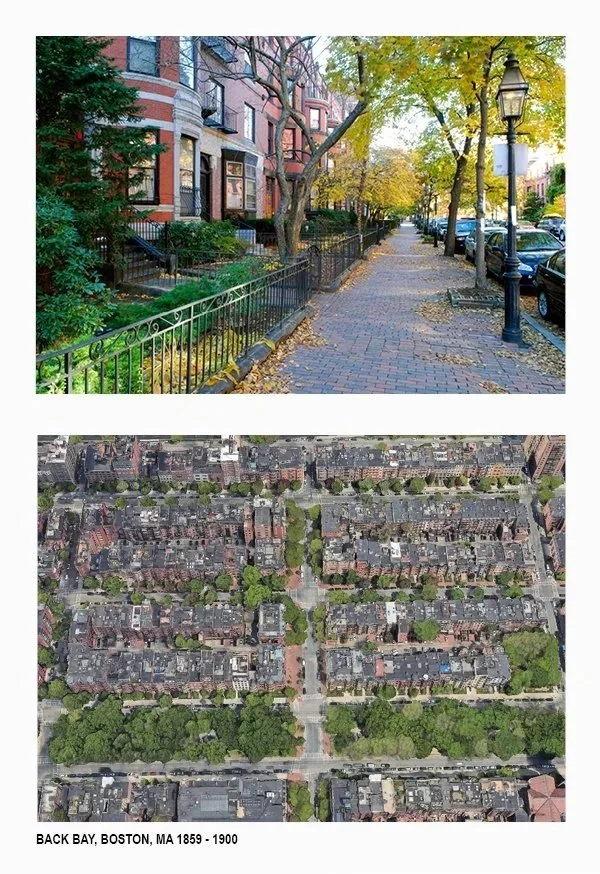

THE BACK BAY NEIGHBORHOOD in Boston, MA was also developed on undeveloped land—land fill where the Charles River emptied into the Boston bay--at the edge of an already 200-year-old dense urban city the only major American city developed almost entirely on pre-industrial era planning principles that remains substantially intact.

URBAN OR SUBURBAN? The Back Bay development taking place as it did in the second half of the 19th century and at the height of the industrial era when planners and developers turned against the city, its compact arrangement combined with the demarcation of separate (albeit still attached) homes and extensive greenery along vehicular oriented streets, is as much a “park” setting as an urban one.

The architecture of emerging Los Angeles was fashioned in Revivalist and Beaux-Arts styles that were among the favorites of the City Beautiful movement. Many of these buildings were both upper- and working-class apartment buildings. Apartment dwelling, even for the rich and even for families, though newly accepted in America, was not uncommon and had not yet again become less desirable than-- or looked down upon as inferior to-- having a home on a lot.

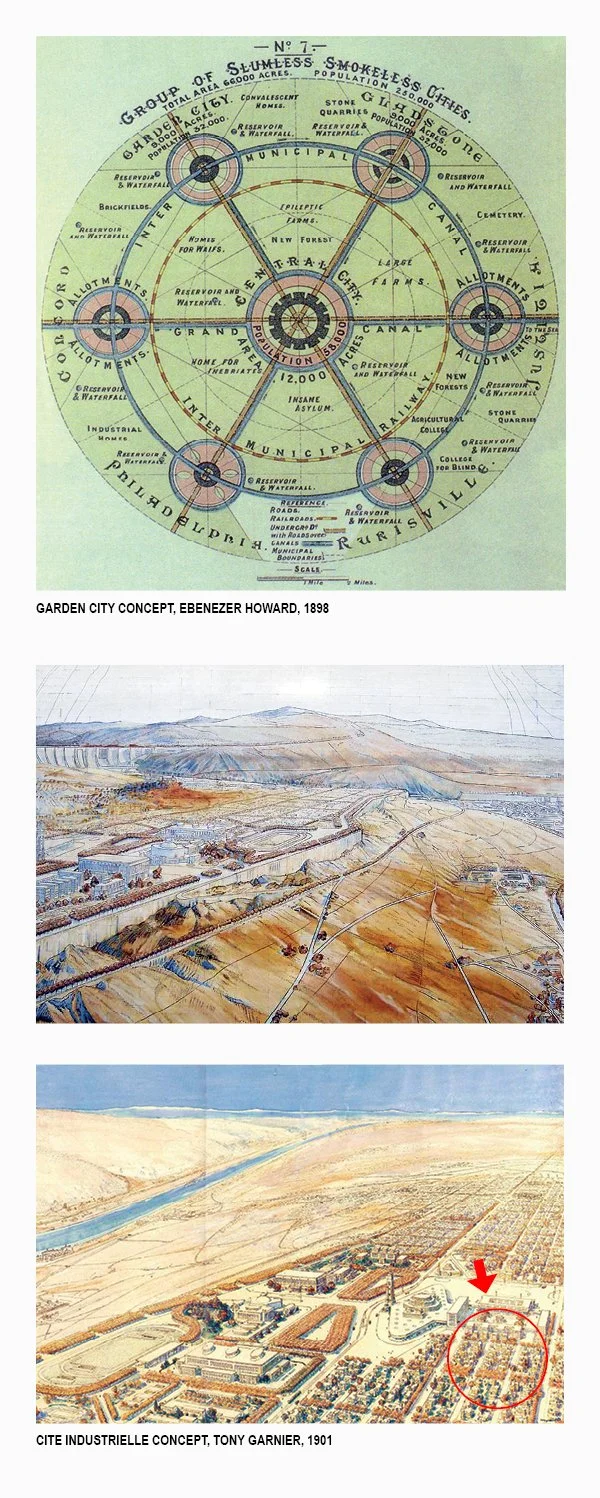

THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY saw the first indications in Europe of the ideological rupture that was to come when urbanists and architects turned against the compact, multi-valent city and toward dispersed, zoned “metropolitan areas” – this just as Los Angeles was ready to take off as a major city.

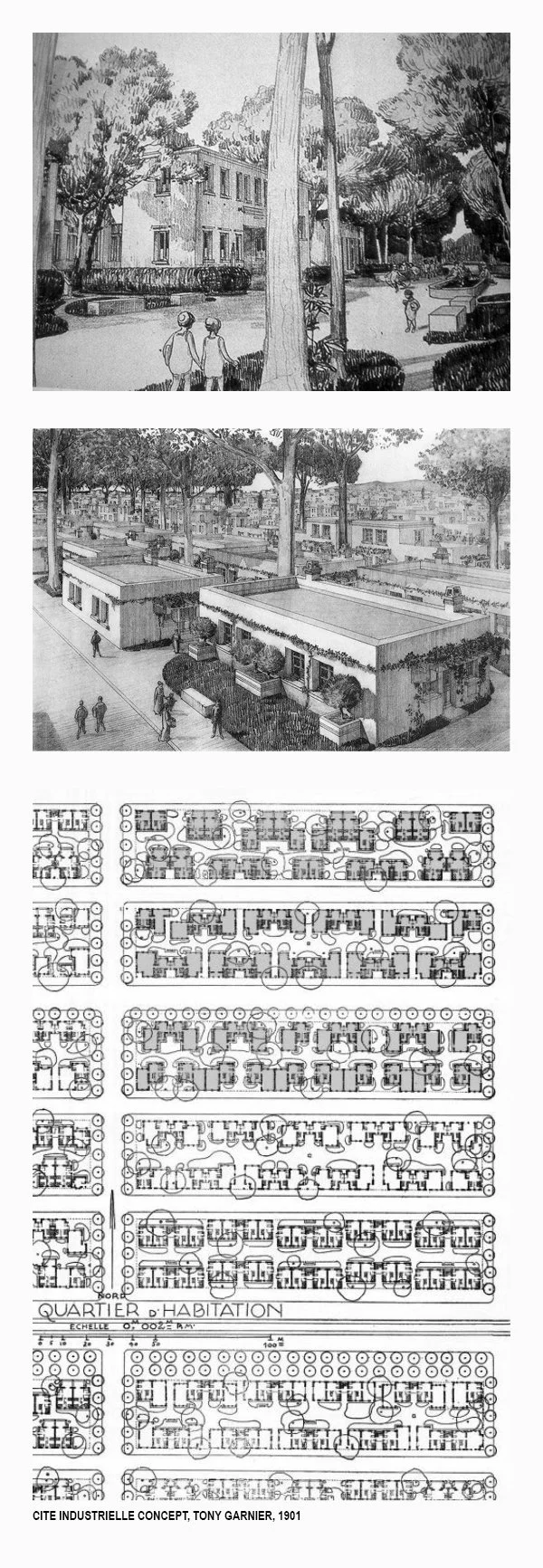

RESIDENTIAL ZONES made up of free-standing houses as distinct “neighborhoods” outside of industrial and commercial zones were first visualized at the turn of the twentieth century perhaps most notably by the Ecole des Beaux Arts trained architect Tony Garnier in his imagining of the Cite Industrielle a roadmap if there ever was one for the modern American metropolis of which Los Angeles is exemplary.

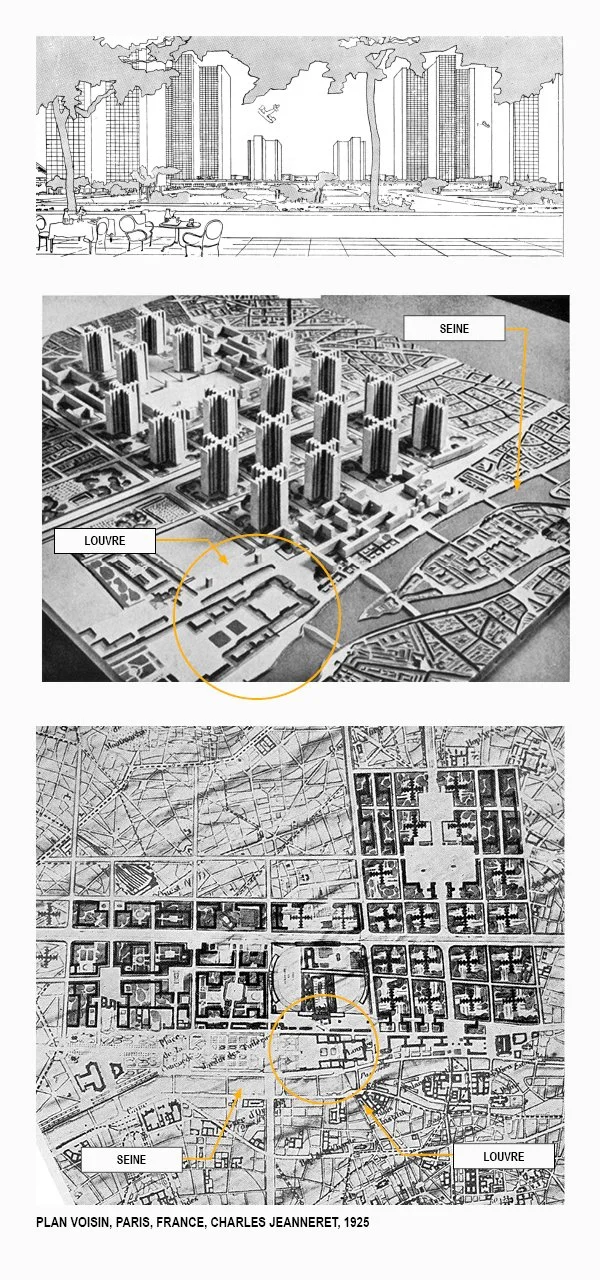

THE HOLLOWING OUT OF THE CITY even centuries-old ones such as Paris was modernism’s final solution in its campaign against 5,000 year old building practices most literally illustrated by the three proposals put forth by Charles Jeanneret in the 1920s one of which was the Plan Voisin a proposal for the redevelopment of the center of Paris published in 1925 just as development of Hancock Park was underway.

From around 1870 to 1920 Los Angeles enthusiastically embraced the aspiration to be like Chicago and New York. It was going to be a world class city rising spontaneously from the dust. It was at first held back by the lack of water and industry and then, curiously, not long after Mulholland had engineered the delivery of water and industry had delivered prosperity, the city paused.

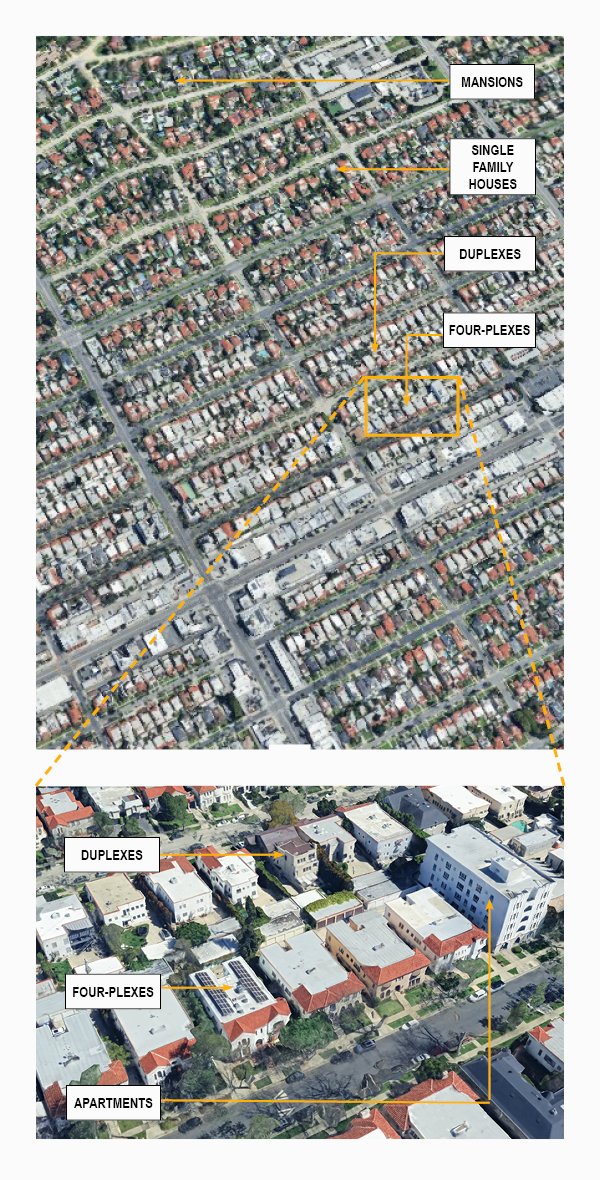

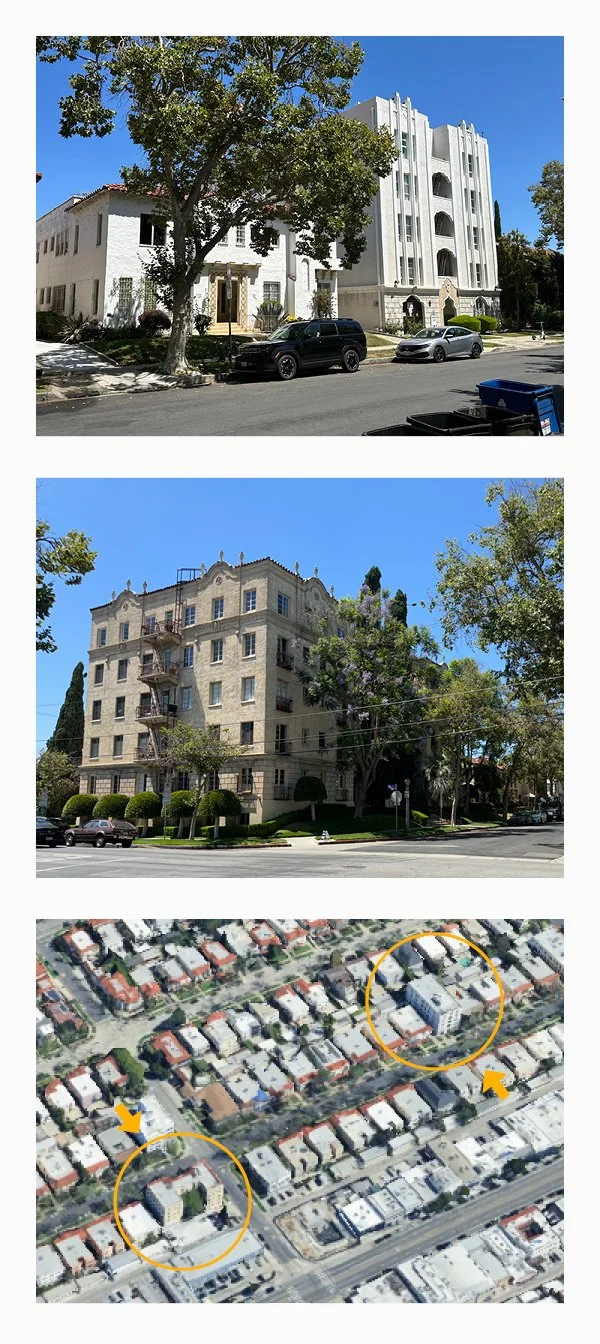

EXPRESSED AS HOUSES ON A LOT the apartment buildings on Sycamore Avenue and the duplexes on Orange Avenue are more closely packed versions of the houses and mansions further east in Hancock Park, presumably to both accommodate and conceal socio-economic diversity in the neighborhood.

Across America industrialization, population explosion and immigration had outpaced older cities’ capacity to absorb or even plan for such challenges. They were congested, dirty and considered unsafe. In the Northeast and Midwest, the city as an idea was increasingly under attack. Just as Los Angeles was emerging as a major city it like the rest of the country began to rethink what a city should be or whether it should be a city at all.

TIGHTLY PACKED FREE-STANDING BUILDINGS masquerade as urban street forming frontages but are belied by the porosity of their arrangement necessitated by driveways between buildings that lead to garages at the rear of the lots, while the sidewalks along the street (or “parkways”) bordered by trees on one side and front yard gardens on the other suggest a path in a park. (Sycamore Avenue, Los Angeles, CA)

That Los Angeles was born of settlers moving onto partially occupied, mostly vacant land bringing with them cultural habits from the east and then, despite not having the problems of those cities of the east, held itself back by doubts imported from the east, is a strange tale indeed, and it explains where I live.

FIVE STORY APARTMENT BUILDINGS proposed in a neighborhood of two-story buildings would today generate nothing but horror and protest, when in fact they contribute to the wealth of both the visual and socio-economic diversity of the neighborhood. (Sycamore Avenue, Los Angeles, CA)

Hancock Park, where I live, lies south of and adjacent to Hollywood, which was in the 1920s the center of the fledgling (and at that time bohemian) movie industry and about four miles west of downtown, which was in the 1920s the center of commerce. It was built as a suburb on agricultural and ranch land butting up against more agricultural and ranch land extending for miles all around.

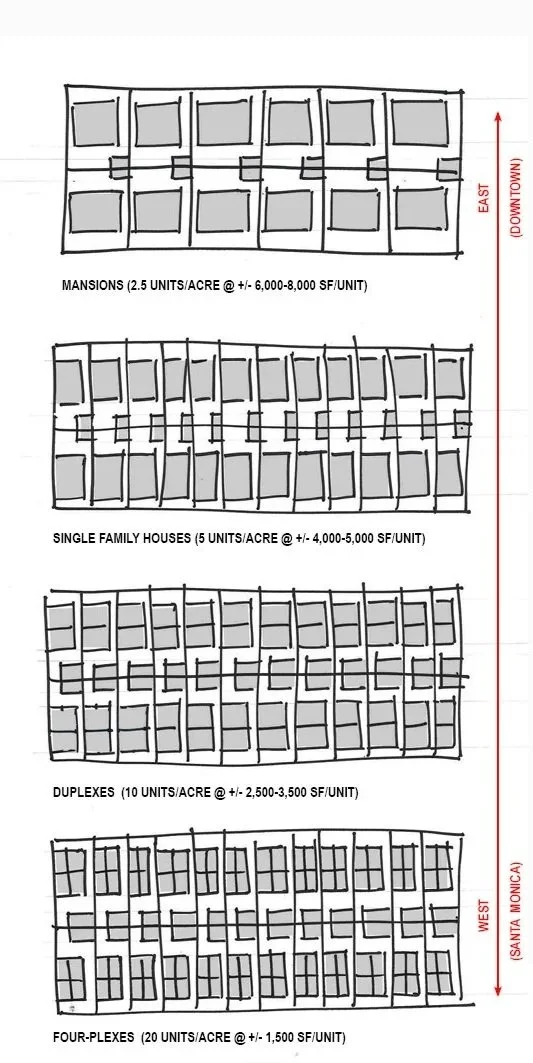

THE INCREASING DENSITY of Hancock Park from mansions in the east to the apartments in the west does not ever cross the line into the kind of urbanism that characterized cities prior to the 20th century. (The mansions, houses, duplexes and fourplexes of the Hancock Park neighborhood, Los Angeles, CA)

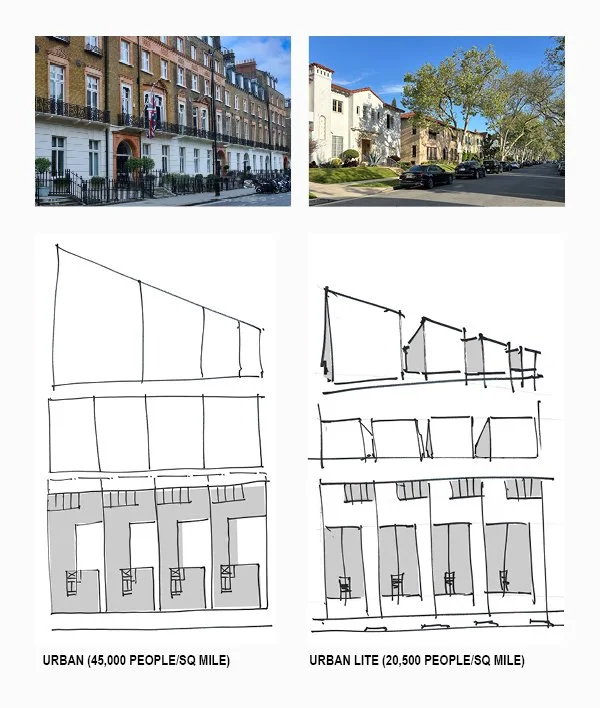

HOWEVER CLOSELY PACKED isolated buildings on lots lined up along streets do not manifest in authentically urban environments in which streets are “carved” out of building blocks (like Boston’s North End and Beacon Hill neighborhoods)

Huge mansions with giant gardens modeled on those found in the Northeast and Midwest occupy the heart of the neighborhood centered around a “country club” (golf course). To the west of these are huge houses with gardens that are divided into two residences—duplexes-- then west of those are huge houses with gardens that divide into four residents---fourplexes. Moving from east to west the houses get more divided and more closely packed. But they all still look (and feel) like houses with gardens.

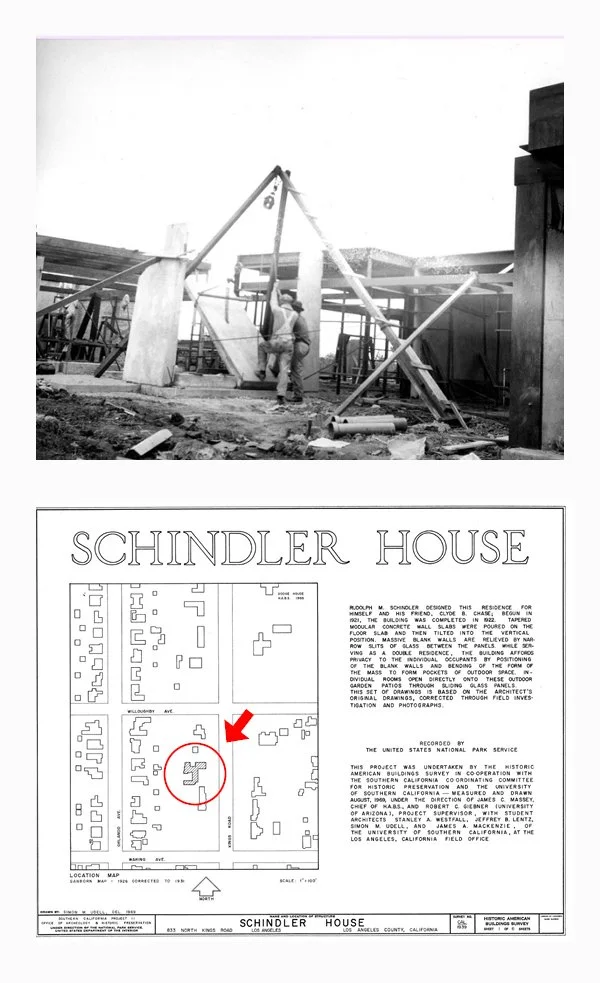

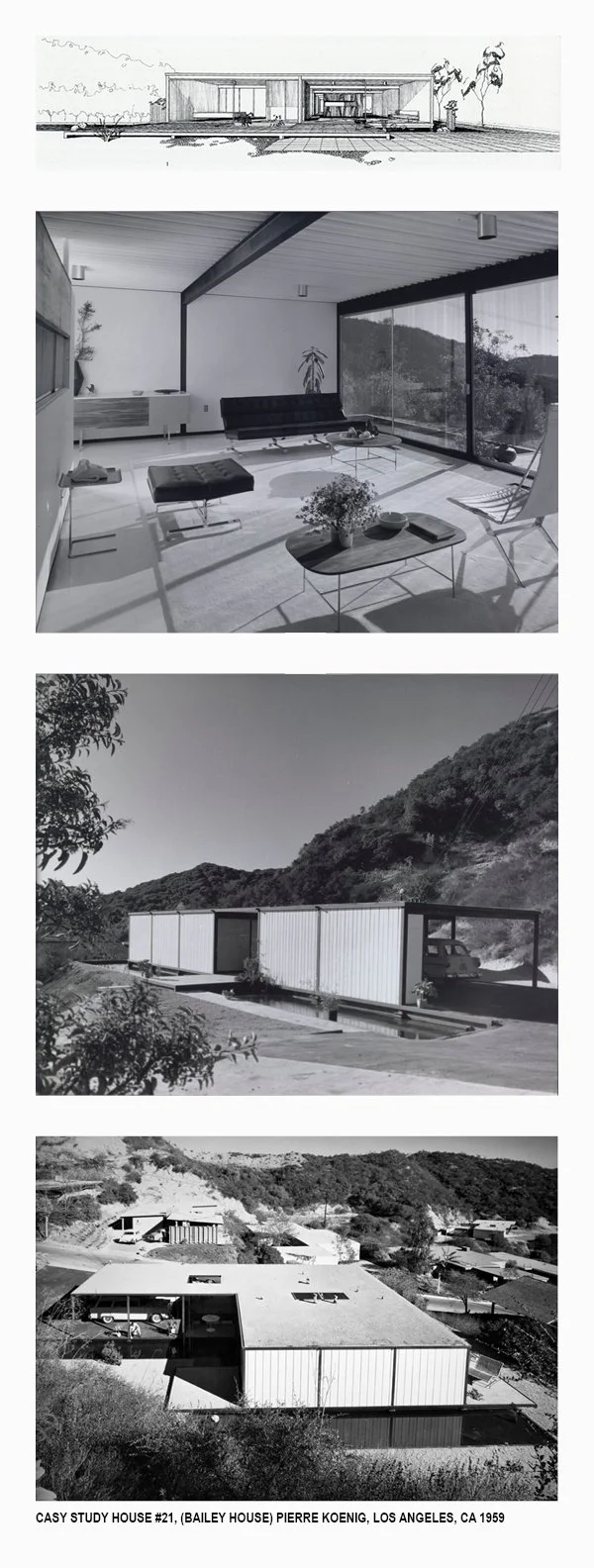

BOHEMIAN MODERNISM had taken root in Los Angeles by the 1920s mostly via the Austrian diaspora (Neutra, Schindler et. al.) and almost entirely within the genre of the single family house, setting the tone from the outset for how modernism would unfold in Los Angeles as mostly a modest, atomized effort.

THE SINGLE-FAMILY HOUSE in the Los Angeles metropolitan area would be for the next half century the focus of architects who either didn’t care about or were oblivious of the impacts of the accumulation of single-family neighborhoods on the environment, the fabric of society and our mental health.

I live in an apartment in a fourplex that’s supposed to (and does) feel like living in a house, a clever way to mask that I’m living in an apartment—the apartment in the late 1920s having once again begun to be seen in America as an inferior way to live. But the “houses” on my street are about fifty feet wide and separated by only about twelve feet (to accommodate driveways). The result is an almost uniform and continuous, almost urban street front, the street feeling like a place to be in as much as on-- like a city, albeit with lots of trees and greenery, like a park.

ALMOST A CENTURY OF EXPERIMENTATION by modern architects devoted almost exclusively to the single-family home in Los Angeles did little more than deliver moderately improved home life for those who could afford it while extinguishing any sense of the city as a home.

Just as the new model of the American city —that we should work downtown and live in the suburbs—promoted as early as the 1850s by such prominent voices back east as Frederick Law Olmsted, was beginning to dominate the American mindset, Hancock Park was in the late 1920s finishing up. On undeveloped land all around Hancock Park, Los Angeles would over the next 100 years expand almost exclusively on the suburban model – freestanding houses connected by cars. Apartments have been a best an afterthought, or at worst a necessary evil.

MID-CENTURY URBANISM in Los Angeles consisted of “garden and tower complexes” were anything but urban, as is most notably exemplified just west of Hancock Park at Park La Brea an obvious copy of Jeanneret’s Parisian proposals from two decades earlier.

GARDEN AND TOWER apartments arranged on this huge site in the middle of the metropolis obliterated the underlying and surrounding orthogonal street geometry not to mention any hope of recovering anything resembling a true urban environment in one of the densest parts of the metropolitan area.

Built as a suburb the neighborhood where I live now rests in the middle of a 5,000 square-mile metropolis, more densely packed than most of the metropolis, in a way that compared to the rest of the metropolis feels like what most Americans would describe as “urban.” And yet I live in a “park” —Hancock Park. urban lite to be sure, but for someone who likes cities, under the circumstances, not so bad.

ZERO LOT LINES meaning buildings, even tall buildings, attached to one another are key to the incremental development of coherent blocks, streets and squares that form a true urban neighborhood. (The future of the Blackwelder-Smiley neighborhood as visualized by Johnson Favaro, 2025)